|

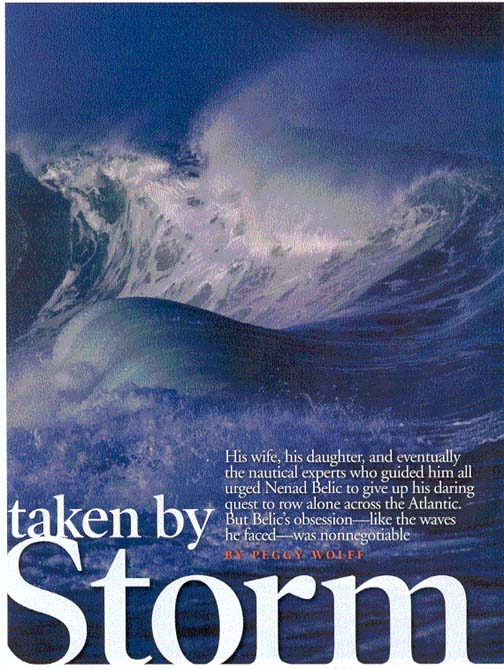

by Peggy Wolff From the rattling window hatch in his tiny boat, all Nenad Belic could see was an undulating, uninterrupted expanse of the Atlantic–a vast oceanscape that he had just rowed. For 137 days, Belic had been crossing the sea, facing backwards as he pulled on the oars for up to 12 hours a day, often battling headwinds and facing swells of 20 feet. He had shaved himself bald for the start of his journey, but after four months, his dark, graying hair had grown in. There wasn't an ounce of fat left on his body. In Lun, his rowboat, the 62-year-old retired Chicago cardiologist couldn't see or smell land, but he was close, just 481 miles off Ireland. When he landed, he would be the first American to have paddled the Atlantic, west to east, from the United States to Europe. But this day–September 24, 2001–when Belic called his oceanographer, Jenifer Clark, by satellite phone, the news was troubling. Clark and her meteorologist husband were guiding Belic's journey using data collected by satellites scanning the earth. And the forecast that Clark read to Belic sounded ominous: "Expect foul weather and dangerously strong winds, anywhere from 20 to 55 miles per hour. . . . Seas could reach 15 to 20 feet. An intense low pressure of 995 millibars will be strengthening and moving toward your position." In the North Atlantic, which is known for its fierce cyclones and strong lows, this was a significant storm, expected to produce high waves–the worst Belic had faced on his journey so far. Clark was worried. She advised Belic to activate his emergency radio beacon, which would bring the British and the Irish Coast Guard to his rescue. "No," Belic told her. "If I do that, they'll pick me up but not the boat." The trip so far had been an adventure beyond anything he had ever expected–the starry sky, the squall clouds that looked like land, the encounters with sea creatures such as dolphins and turtles–and he wasn't prepared to give it up. "What would happen if Lun capsized?" Clark asked. "That is very possible with this incoming weather system." Clark was frustrated. Belic had hired the world's expert on the Gulf Stream current, but wasn't heeding her most important advice. "Nothing is tied down, and that would be a mess," Belic admitted. But he assured her that the little boat would float like a cork no matter what. Their satellite line was cut four times before they finished their conversation. The forecast turned out to be correct: The seas kicked mounds of water and the waves exploded, but Belic rowed through the storm without capsizing. His luck had held again. But another storm was building right behind, and this one would be different. There would be something meteorologists call an ocean surge, a very strong spike of high waves that come through over a period of six to eight hours. Again, Belic would face it alone, while murderous masses of water pounded like cannonballs against his boat. * * * This is the story of one man's obsession–a dream that probably stretched back to an exotic childhood and drove Nenad Belic to defy the wishes and advice of his family, friends, and colleagues. The quest began on May 11, 2001, from Stage Harbor, in Chatham, Massachusetts, a place they call the "elbow" of Cape Cod. In a 21-foot, custom-designed rowboat–with no sail or engine to aid him–Belic began a voyage of 2,580 miles to the Portuguese shore. His goal was to get there before September, when hurricane season hits and the raging storms produce, in the dry terms of naval vocabulary, nonnegotiable waves. At the start, he expected that the crossing would take him 100-odd days. It was a journey epic and reckless, admirable, and a bit mad. * * * Nenad Belic's wife, Ellen, didn't want him to make this trip, but on Sunday, May 6th, she threw him a bon voyage party at their Lincoln Park home. The emotional highlight of the evening came when the 30 dinner guests gathered around the dessert: a tremendous sheet cake decorated to look like an ocean. A little yellow rowboat, with Lun–from the Latin for "moon"–written on its front, cut through the creamy blue frosted waves, one large seagull hovering close to the boat, its wings stretched to the full. A good omen. Seagulls stay close to shore. Belic's two sons from his first marriage, Adrian, 32, and Roko, 30, are filmmakers (they earned a 2000 Academy Award nomination for the documentary Genghis Blues ), and throughout the party they videotaped their father, peppering him with questions about his adventure. At five feet eight inches and stocked with muscles, Belic looked like an explorer in the classic mold–with squint lines between his brown eyes; bold, black eyebrows; and a dimple in the chin that seemed the central fact of his face, a mark of his determined nature. He talked to the camera in a gentle voice, yet there was no answer to the Big Question: What in the world brought this on? Belic just shrugged his shoulders, pushing his charm to the limit, his eyes lighting up as they always did when he talked about his trip. Fellow Yugoslav George Matavulj, a friend of 30 years, offers a possible answer: "Once he accomplished this, he would come back, and it would be with him." Belic didn't really care about setting a new record for days at sea, and he wasn't looking for publicity, since he shunned the press and refused to have a Web site or sponsor. "It would be something he could cherish for the rest of his life," Matavulj says. "Something to hang on to. I mean, consider this: He never wanted to be a doctor in the first place." He had wanted a life at sea. * * * To sit in Belic's home office was to see a person quite apart from the successful cardiologist he had become. Until retiring in 1999, he had served for 12 years as medical director of the Heart Station at Columbus Hospital; he had also been in private practice with the Lake Shore Cardiology Group since 1986. Patients adored him and enjoyed his affectionate, teasing manner. The staff admired him for seeing impoverished people "off the books." Still, as his partner David Koenigsberg put it, echoing an observation made by many others, "[Y]ou know someone, but then you don't know them." Belic's home office let it all hang out. The place was a private cocoon of computers, impressionistic oils of Yugoslavian harbors, and surrealistic collages created by Belic himself. Odds and ends of marine supplies lay about, along with tubes of sealant, coils of braided dock line, and an exercise log of hours spent on the rowing machine. Sitting in his leather chair, Belic could admire a photograph of his father, Zivan, smoking a pipe on his own boat, or consider one of the many inspiring sayings tacked on the walls, such as: Each man must look

to himself to teach him the meaning of life. –Antoine de Saint-Exupéry * * * Belic's younger brother, Predrag, says that nothing in Nenad's background seemed to have prepared him for the grueling dangers of rowing an ocean, except being raised as a child of divorced parents in Yugoslavia in the shadow of World War II. Nenad's mother left home when he was a few months old. He was six when the war ended, and it was a time when difficulty lurked everywhere. "People were disappearing into the woods with the Partisans, the Communist resistance, or being killed," Predrag says. "Nenad had a very firm inner core. He grew up at a time when people weren't afraid of losing their lives." From his memoirs, set down in 1999, Belic's deep love for the Adriatic comes through: "We lived in a beautiful old house on a hill with a view of the Rijeka harbor from a large balcony. . . . I was passionate about ships; every day after school I'd scan the port of Rijeka with binoculars, and meticulously record all the ships in port, and those on anchor, and sketch any new company insignia noted on ship's funnels in my log book. By the time I was 13, I decided to become a merchant marine captain." * * * His father talked him out of that career just before the boy would have registered for maritime school, arguing that there would be a better future for him in medicine. In Zagreb, Belic grew up very self-reliant. His father's business travels and healthy appetite for women often left the teenager alone. It was Zivan's doctrine, Nenad recalled, to have three girlfriends at all times, plus or minus a wife. So the father and son made an agreement: As long as the boy got good grades and stayed out of trouble with the police, they would live like equals. Nenad would simply take cash as he needed it from an envelope that was left in a top desk drawer. When Belic was about 19, and already studying medicine at Zagreb University, he and his father moved to a small apartment; they would leave notes for each other on a bulletin board in the hall. Despite many such moves, life was good, especially by Yugoslav standards. Belic rode around on a Vespa, and had a small circle of like-minded friends who enjoyed jazz and making Super8 movies. After graduating from medical school and completing military service, Belic moved to Seattle with his new Czech wife, Daníca. There he completed his internship at Providence Hospital, followed by his residency at Seattle's Virginia Mason Medical Center. In 1971, Belic arrived at Chicago's Northwestern Memorial Hospital for a fellowship in cardiology. He had had two sons with Daníca, Adrian and Roko, but the couple had separated when the boys were still young. In 1983, he met Ellen Stone, now a psychotherapist and professor of psychotherapy at Columbia College. They married soon after, and had two daughters, Dara, now 18, and Maia, 13. * * * Though Belic had dreamed of the sea since he was a boy, Ellen Stone Belic thinks the specific idea of rowing the Atlantic first came into his head in 1989, when the family vacationed on the Adriatic island of Rab for his 50th birthday. To celebrate the occasion, Belic decided to row around the 35-mile shoreline, just as Zivan Belic had done years earlier. Concerned for Nenad's safety, his father and friends wanted to follow him around the island in a motorboat, but Nenad wanted to be alone. The steep, rocky banks enclosed protective harbors that helped him elude his entourage. After that adventure, it wasn't long before Belic found Philip Bolger, a well-known boat designer from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Bolger came up with a unique design for Lun. The hull, which had long, seaworthy lines, would be covered with a canopy, with solar panels and a hatch on top. The idea was to keep the oarsman out of the sun, wind, spray, and salt, thus avoiding some of the discomforts that plague rowers who sit unprotected in open cockpits. With an interior width of only five feet, the boat had few creature comforts. Belic would face the stern on a sliding seat that could be lifted off its tracks so he could set down a sleeping bag at night. There were compartments with room for water, dehydrated military meals, and gear. The oars poked out of specially built ports on each side, and Belic could sit in the high-tech cockpit and look out windows above shoulder height. Belic took Bolger's plans to Steve Najjar, a California boatbuilder, who spent a year constructing the craft. Najjar cross-laminated three layers of cedar, and by using so much lumber, he was certain that even if Lun filled up with water, the buoyancy in the wood would float the boat. Even with Lun ready to go, Ellen forbade Belic to tackle the Atlantic. "I told him absolutely not; the kids were little; it was crazy," she recalls. For a while, he satisfied himself by rowing Lake Michigan to Mackinac. "But obviously he had kept this Atlantic idea stored somewhere in his memory," Ellen says, "and it had been percolating there for a number of years." When Belic retired from his cardiology practice at age 59, he began preparing for his Atlantic row, the dream he had been talking about for ten years. He convinced Ellen that he would never feel complete unless he attempted the row, but that he would take every precaution for his safety. He spent the next two years preparing: reading maritime stories, taking a ham radio course, studying Morse code, and learning how to read weather charts and patterns. He added celestial navigation classes at the Adler Planetarium & Astronomy Museum to the standard weight training/rowing menu at the East Bank Club, then ordered the necessary safety equipment, plus the military food rations and a little stove. Finally, he hired Jenifer Clark, and took a weekend seminar in the spring of 2001 at her Maryland home. She taught Belic about the bottom of the atmosphere, the sea surface and its favorable currents; her husband, Dane, dealt with the top of the atmosphere, the weather patterns. On board his boat, Belic would receive their updates via satellite phone. As the time for departure got closer, Ellen felt racked, and she tried to talk Nenad out of going. She and others told him to postpone the trip for a year to help manage the turmoil of raising the couple's teenage daughters. But Belic had been sitting with this dream all those years, and there was no stopping him now. * * * Weather conditions were perfect when Belic slipped Lun into the water at Pease Boat Works, in Chatham, Massachusetts, on May 11th last year. His sons, Adrian and Roko, rode in the motorboat that towed him through the channel. As the graveled harbor bottom fell off, Belic's sons unlashed the rope, then watched while their dad set up the oars, stroked a few times, and coasted, much like a newly hatched bird trying to stand up and move its wings, as Adrian recalled. The motorboat followed Lun out, going in circles around the craft until the sons got "beyond the continent," where they gradually fell astern. They cut the engine, then watched their father slowly, slowly row until he disappeared. Lun looked like a little yellow submarine. Soon afterwards, Ellen got a phone call at home: "Who is this guy out here?" demanded Thomas Craig, a search and rescue controller with the U.S. Coast Guard at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Craig had learned of Belic's departure from a local newspaper reporter who had interviewed Belic at the dock. "Tell him to come back!" Craig shouted to Ellen. He wanted Coast Guard personnel to inspect Lun from a safety standpoint. "You have my permission to send a helicopter and bring him back!" Ellen told him. Today, Craig says, "What did I know before he left? Nothing! I don't even know if he had a life jacket!" The U.S. Coast Guard has the right to determine if a vessel leaving the United States is seaworthy and to terminate the voyage if it is not. Craig wanted to know, did Belic have an EPIRB–a registered emergency position-indicating radio beacon? Had he filed a float plan? What was his expected course? What equipment did he have on board? Belic had told Ellen that when he registered his EPIRB in Cleveland, no one had advised him to check in with the Coast Guard on the eastern seaboard. Days later, when Belic and Lun were out of Craig's territory and into the larger offshore area patrolled by the Coast Guard Atlantic Area Command Center in Virginia, Belic said he had called in. After he described his safety and communications equipment–emergency flotation balloons, two water desalination kits, foghorns, a Global Positioning System, a shortwave radio, and a satellite phone, plus the necessary ankle and finger splints, syringes, needles, and local anesthetics–the Coast Guard was satisfied. That first day, Belic was soon out on the benign and gentle sea, gliding well beyond the breakwater. The salty air filled his lungs as he began living the first page of a fairy tale he had written years earlier. The Atlantic remained calm and he rowed all afternoon, snacking on Spam, bagel chips, and water, probably listening to a classical music station from Boston. He wasn't interested in news or talk shows anymore. After dinner, he deployed his sea anchor, an underwater parachute that would prevent him from being swept back by the wind or the current swirling around the eastern coastline. During his rows to Mackinac, he had written in his logbook, "Sleeping on a small boat is wonderfully restful, although one wakes up many times during the night due to an unusually high or noisy wave bumping on the sides, or from the beeping of the radar detector." The next morning, Belic drank some instant coffee with halvah and dried fruit, pulled up his sea anchor, and rowed steadily east to catch the consistently warmer 80-degree water of the Gulf Stream, the powerful ocean current that pushes north from Florida, hugs the coast until North Carolina, then turns northeast towards Europe. To get into the Gulf Stream is to hitch a ride, up to 100 miles a day, without even touching an oar. But for three weeks, Belic encountered winds literally blowing him backwards, making him row full tilt just to inch ahead a ridiculous few feet. Jenifer and Dane Clark had warned Belic about the problem. They had urged him to leave from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. There, he could pick up the Gulf Stream a few miles offshore. But Belic had only smiled politely and shrugged his shoulders. Dane had also advised Belic not to leave as early as May 11th, but to wait a week, until the winds and seas calmed down. But Belic's mind had been set. He wanted to leave from Cape Cod. After all, other ocean rowers had done it before. Now, all Belic could do was wait out the winds–as he put it, "sitting on a sea anchor, rocking and rolling, fattening up on Spam." Still, even though he was being pushed southwest towards New York, far from the Gulf Stream in chill 40-degree air, his spirits remained high. Speaking to him twice weekly by satellite phone, Jenifer saw the first signs of his stubbornness. She tried to persuade him to go back, truck his boat down to Cape Hatteras, and start over. By then, she had seen the prediction from the National Weather Service Forecast Offices for a higher than normal number of hurricanes in the northern Atlantic. He had to get going, Jenifer thought, or try again the next year. But she couldn't change his mind. Nor could Ellen, who also spoke to him regularly by satellite phone. "The Greeks would say that the gods are trying to tell you something, Neno," she said, using his nickname. He offered no response. * * * On May 31st, at only 89 miles out, Belic e-mailed his buddy list: "Finally Moving East All Systems The Boat And I Are In Good Shape Been Visited By Seals Dolphins Sharks And Innumerable Birds All Friendly All Is Well This Is Good Fun Cheers Nenad." The writing was cryptic, but all seemed well within the vaguely suspended rules of naval electronic communication. At last, the weather had improved, and for the next few weeks Belic moved swiftly east, up to 40 miles a day. His long trip could now be followed on www.oceanrowing.com, the Web site of the Ocean Rowing Society, a London-based organization directed by Kenneth Crutchlow that tracks the progress of ocean rowers. On June 23rd, Lun was spotted by the 73-foot sailboat Renaissance en route to Ireland from Newport. "Pirates!" Ken Campia was startled by his daughters' shouts, so he ran up on deck, and, out on the calm, flat seas, in the late morning sun, he saw a tiny yellow speck on the horizon. "Our pirate turned out to be a man . . . a few hundred yards away, with a flashing strobe light, rowing a yellow ocean craft called Lun, registered out of Chicago of all places," Campia wrote in his logbook. "It certainly seemed like a very strange thing to come upon at sea–a cigar-shaped object with solar panels and hatches on the top." Campia's family, from Lake Forest, were on a summer vacation. "We traded him a few oranges for a quick health consult, chatted for a half hour, offered to give him a tow, he said no, we asked if we could do anything, then it was time to go." In his logbook for that day, Campia wrote, "You can make your own derivations of the [boat's] name, we certainly did." For the Campias, Lun was short for "lunacy." Seven hundred forty-three miles rowed, 2,144 to go. In his phone calls home, Belic would sometimes say that the horizon looked so close, it was as if he were on a big pond. He was not listening to any of the CDs he downloaded, and not Moby Dick on tape, because, he said, it distracted him. It interfered with the sound of the sea, with the rhythm of rowing. He was listening to BBC Radio, remembering his childhood, and whistling familiar tunes, all within a very routine day: up at dawn, eat breakfast, row three or four hours, eat lunch, row, eat dinner, go to sleep. Ellen thought her emotionally distant husband was becoming one with his boat, growing daily more tranquil and enmeshed, at once more crazy and more mellow. Though she was mentally worn out from having lived with his obsession for 12 years, she actually started feeling better after he left. The arguing and the tension stopped. The summer plans for their teenage girls were made. Although she had never warmed up to Belic's venture, with him gone she was able to put her own resources to work to head a committee to rewrite the Columbia College bylaws and meet her own part-time schedule of seeing patients. By pulling her emotional life together through meditation, a writing workshop, a Buddhist retreat, and seeing friends, she could try, as she put it, to "metabolize" the feelings of having been abandoned and of having to carry the emotional burden on her own. Their daughter Maia, a Francis Parker eighth grader, was on a teen tour out West, and although she was aware of the risks–her dad had shown her all his safety equipment–she always believed that he would come home. But Dara, who had just completed her junior year at Parker, had difficulty with his leaving. They fought about it a lot. She always felt as if he wouldn't come back. But perhaps Belic's long days at sea bred a sociable streak. Out of nowhere, he volunteered to take ballroom dancing lessons with Ellen when he returned. Ellen thought he might be homesick. Maybe he missed her. * * * By the end of July, with the wind and currents pushing him, he was moving farther north than he had anticipated. His long ocean crossing was now leading to a landfall in France. He had come 1,926 miles in 81 days. Then he got on the wrong side of an eddy, a circular mass of water that flowed clockwise, like a record 60 miles wide spinning in the water. "It's a gorgeous day, the sun is shining, there's no wind and I'm going backwards!" he told Ellen. He was sucked in twice before he could row hard enough to escape the eddy's two-knot current. Even though it had set him back four days, he didn't complain. His cup was always half full. But on August 22nd, he took an inventory of his packaged military meals and realized that–even if he stretched it–he could go only four more weeks. He was still 900 miles from France, a distance of at least 30 days' rowing. From Chicago, Ellen took command–not wanting him to starve out there, even if she did wish the trip were over. Immediately, e-mails flew across the sea to Kenneth Crutchlow at the Ocean Rowing Society. What were the options? Crutchlow's organization assisted only rowers who were within 300 miles of shore. Sending out a private yacht from Brest, France, packed with freeze-dried French food would be horribly expensive. With winds shifting again on the unpredictable seas, it now looked as if Lun was headed for the British shore. But a response from Her Majesty's Coast Guard Falmouth presented its own problems. If the Coast Guard sent a ship, the press would follow; and if the Coast Guard did the resupply, a rescue would usually be not far behind. While Ellen and Crutchlow monitored Belic's progress over the next couple of weeks, there was a lot of e-mail discussion about resupplying food–such as the etiquette of requesting food from a passing ship, or the high risk of a successful airdrop. On September 13th, Belic contacted a passing container ship and was rewarded with a styrofoam lunch box: a tin of Spam, a loaf of freezer-burned white bread, and some water. Then, on September 18th, the captain of the Swedish container ship Rigoletto received a call on VHF radio from five miles away: "I am ocean rowing boat Lun calling the ship on my starboard side head east. Please come in." The message continued: "Departed from Cape Cod 100-odd days ago headed for Europe. It is taking longer than I expected; could you spare me some food?" The captain radioed back, and while it was a tricky maneuver to slip alongside a rowboat, the Rigoletto's cook pulled out the gangway and sent down a sack of food: ravioli, baked beans, corned beef, sausages, fruits, cheese, and the hard Swedish bread knäckebröd. Belic was thrilled. Being treated to a gourmet food drop prompted a call home and a boast about his breakfast of hot pork tenderloins in mushroom sauce. The Rigoletto left Lun in her wake. * * * On Monday, September 24th, Belic called Jenifer Clark on the satellite phone at 10 a.m., just as he had done every Monday and Thursday since the middle of May. Jenifer, using satellites to sight nature's warnings, issued a strong alert that the barometer was dropping and seas would be building. After reading him the forecast–and warning that wind gusts could hit 40 to 50 knots–she advised him to push his EPIRB. This would have been the toughest storm he had endured yet. He refused. "Like he really didn't believe anything would ever happen to him," she says. "He felt falsely secure Lun would protect him no matter what." Despite the safety features in his boat, Belic had no harness to strap himself down, no survival suit, no life raft, no spare EPIRB, and nothing tied down. All he had against the sea's power were his boat and his human values: his intelligence, his experience, and his stubborn will to win. That very same day, Ellen had a sinking feeling, and when he called, she begged him to stop the trip. She had been arguing with him the week before to leave the boat, and he was cross. "Please call for help," she urged him. "You've been lucky with the weather so far. You decide your own success, Neno. You are the rower who holds a record for being in the water the longest. You are the oldest to attempt this. You can stop now." "I can't," was all he said. As it turned out, the low-pressure areas associated with fierce sea weather stayed north of Belic, and he navigated safely through the storm he faced. Belic had come 2,535 miles from Cape Cod. He had only 481 miles to go. He had made one concession: He was now likely to land on the rough Irish coast, and knowing that the rocks there could grind a boat to bits, he had agreed to Crutchlow's offer for a tow from 24 miles out, the distance at which land could be seen. Dane Clark advised him that other storms were coming that week, but Belic chose to wait them out. He deployed his sea anchor and faced the storms alone. "He said the waves were really big, but he didn't sound scared," recalls Roko, who spoke to him on September 26th by satellite phone. On Thursday, September 27th, Belic made three calls: to Ellen, who said she would pray for him at Yom Kippur services that day; to Crutchlow, leaving a message saying that the weather was beastly, but that he was fine; and to Jenifer Clark. He didn't call her at the usual time of 10 a.m. She waited until 10:45, then left a warning for him on her answering machine: "Very complicated weather pattern over the eastern North Atlantic . . . indications that a . . . low-pressure area will develop over the weekend and be centered near 57N 23W by Sunday with the pressure as low as 950 mb!" "Nine hundred fifty millibars! It's off the dial!" says Belic's friend George Matavulj, who tracked Lun's progress on the Internet every day at the Glencoe boating house. Matavulj and Belic had sailed together for years, and Matavulj is sure Belic knew the impending danger. Indeed, Matavulj had told his friend to push the panic button if the barometer ever fell that low. Jenifer Clark had warned Belic of other storms, but these storms spread across hundreds of miles and did not center in his location. Belic probably believed that he would get through this storm, too. Today, no one knows exactly the ferocity of the weather, but in a six- to eight-hour period of time, Dane Clark says, the winds that blew from the North Atlantic towards Ireland on Sunday, September 30th, pushed the waves to rise from around 15 feet high to around 30 feet. Some observers suspect that a Perfect Storm situation came up, in which two wave jams–waves steep and close together–become bigger and more violent until they meet in a rogue wave: one steep, 50- or 60-foot wall of water, avalanching over the boat. At 10:30 that night, the Irish Coast Guard and HM Coast Guard Falmouth picked up an EPIRB distress signal from Belic's last position, near 51N 15W, placing him 259 miles west of Bantry Bay, Ireland. The beacon could not have been activated accidentally. Belic would have had to pull the EPIRB off a bracket, flip up a cover switch, reach in, and flip the main switch. At 11:10 p.m., a Royal Air Force Nimrod aircraft located the beacon's flashing light, then circled the area until an RAF rescue helicopter arrived a few hours later. In darkness, amid gale force winds, the RAF dropped two life rafts. The airmen anticipated finding the boat and the rower, but all they saw was the flashing beacon. There was no sign of a boat or debris. After 143 days at sea, Lun and Belic had vanished. The EPIRB signal, which was relayed throughout the Coast Guard system, prompted the Great Lakes Coast Guard in Cleveland to call Ellen. It reached her on her cell phone at the Chicago Historical Society, where she was spending that Sunday afternoon. A massive rescue operation had been launched, but if Belic was in the 60-degree water without a survival suit, he wouldn't survive more than two hours. Shortly after midnight that night, Ellen felt her body enveloped by a warm, loving presence that held her for a few moments and then was gone–"as if he had come to say goodbye," Ellen says. That same night, their daughter Dara, away at school, had a nightmare that her father had drowned. * * * After 17 hours of searching in 58-knot winds and rough seas, the British Coast Guard called off the effort. Belic's father-in-law, Jerome Stone, the chairman emeritus of the packaging manufacturer Smurfit-Stone Container Corporation, set up a command post at Ellen's home, trying to use high-level connections in government or business to pressure the British and the Irish Coast Guard to resume the search. Some family members thought it was already too late, because they knew Belic would have activated his beacon only at the last possible moment. But Jerome Stone lined up his task force anyway. Among many others, there were Sugar Rautbord, with connections at the Irish Daily Mail and in British Parliament; the president of Jefferson Smurfit, the Ireland-based company with which Stone Container had merged; and Newton Minow, a prominent Chicago lawyer and former head of the Federal Communications Commission. "Newt, I'm leaning on you as a last resort," Stone said. Minow called North Shore congresswoman Jan Schakowsky, and she urged both the British and Irish ambassadors to resume the search. Finally, Irish Coast Guard commander Eamon Torpay called Stone with good news: Yes, they would continue the search one more day. Then Stone insisted on yet another day, and got it, while Belic's son Adrian, who was in Ireland to keep people mobilized for the search, found a private firm, Diplomat Freight Services, to search east of the Irish Coast Guard's grid. Belic's rowboat would track with the wind; it could drift 90 miles a day. Though his communications were cut, he could be trapped in the boat and if his water desalinator was working, he could still be alive. Other lost rowers had reported planes flying over them several times before they were spotted. But even after the weather cleared, no one sighted the rower and his boat–not the Irish townspeople along the shore, nor the low-flying aircraft, nor the fleets of Spanish fishing vessels that traffic the international waters off Ireland. Six weeks later, Irish fishermen on board the Molly Bawn spotted what they thought was a dead whale. It was Lun, upside down a quarter mile offshore at Pouladay Rocks, about six miles from Kilkee, County Clare. A diving inspection by the Kilkee Sub-Aqua Club found no body, but Lun, still intact, had sea encrustations growing inside. She had been upturned that way for a long time. Nenad had never wanted the Coast Guard to pick him up and force him to abandon his boat. Now the Coast Guard towed in the boat, but not him. * * * On December 16th, the same day that friends and family held a memorial service for Nenad Belic in Chicago, a volunteer and three hefty men from the Kilkee Rescue Service in Ireland went out in a rescue boat to the exact coordinates where Lun had been found. As they shut off the engine, the heavy overcast clouds parted and the sun shone through. One of the men placed a floral wreath in the water, then pulled away, turning around to watch the flowers break off one by one and leave a trail. The four men said nothing all the way back. If it was gut-wrenching for strangers to see Belic's dream die, it was heartbreaking for his family. Although part of Ellen was relieved that the ordeal was over, she still felt she could have said something to persuade her husband to give up his quest. "Maybe I should have said this; what if I had said that?" she wondered. "What interpretation could I have made that would have helped him see the danger he was in?" At the memorial service at Chicago Sinai Congregation, on Delaware at State Street, a stranger came to the open mike. She had followed Belic's lone passage on the Internet and had driven seven hours from Kentucky to say goodbye. Her name was Tori Murden, and Belic would have known her face from the video that Jenifer Clark had shown him at her weekend seminar. Murden had rowed her American Pearl across the ocean in 1998, and, as the swells grew in September, she got caught in Hurricane Bonnie and then rowed straight into Hurricane Danielle–a crisis that was later re-enacted for the Discovery Channel. Bracing against the walls of her cabin, she dislocated her shoulder, capsized several times, and after a couple of days of being battered, deployed her distress beacon for help. "I know the part of Belic that had to go row an ocean," she told the mourners in a trembling voice. "I think of the story of Icarus. . . . 'And my friends always warned me never to fly too close to the sun. But as soon as I went out flying, I headed for that light.' This story was published in March 2002 issue of Chicago magazine |

|